The Tumult in MLPs

If the recent violent sell-off in energy infrastructure stocks has you puzzled, you have plenty of company. That’s why Sunday’s blog is going out early, because we’ve been discussing it with so many people. We enjoy a regular dialogue with many of our investors and last week was the busiest we can recall in responding to clients.

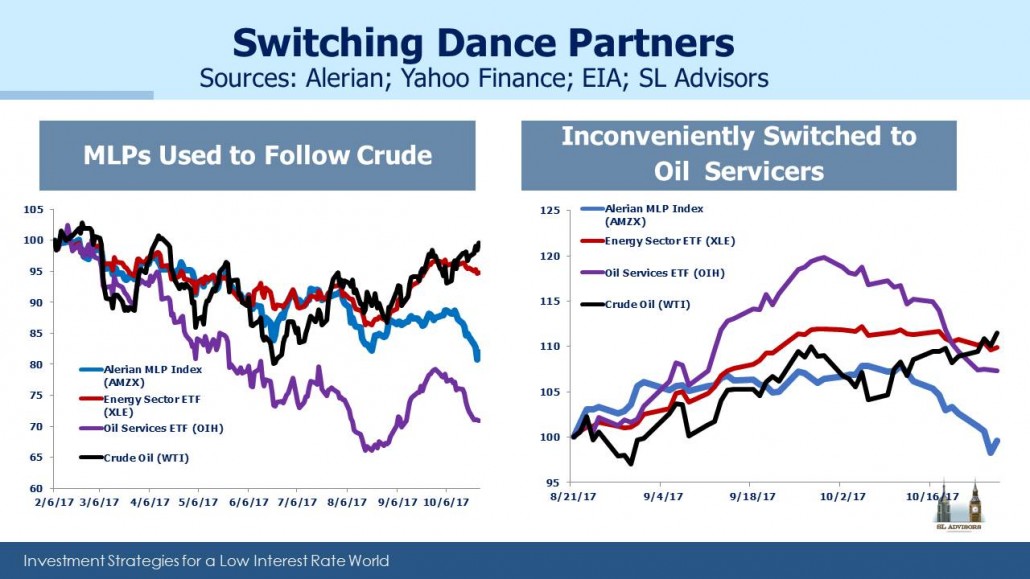

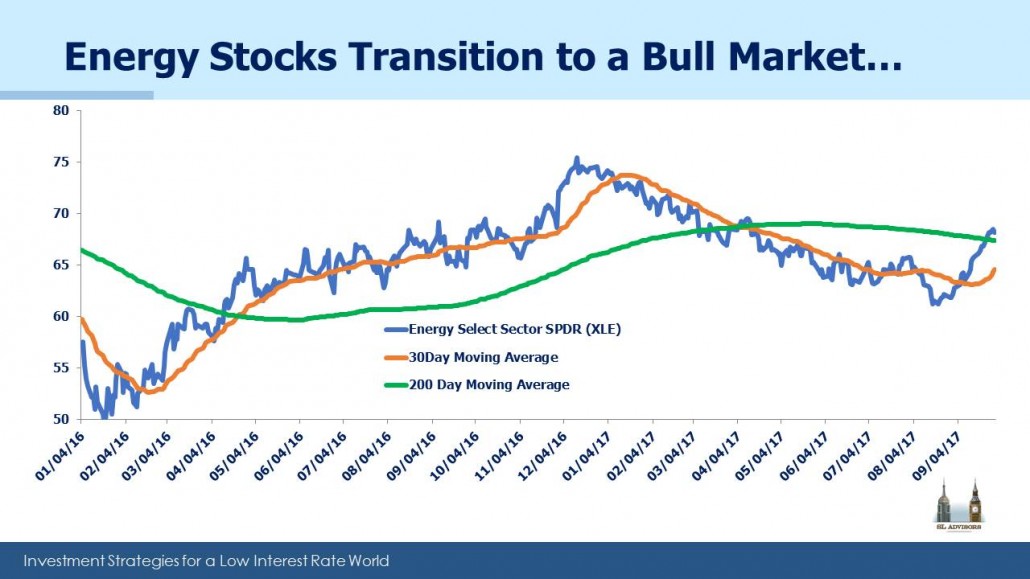

Many wanted to understand why MLPs had followed crude oil lower earlier in the year but failed to mimic its recent recovery. It’s easy to sympathize. A bullish view on oil was almost a prerequisite to committing capital to the sector in the first half of the year. Never mind that linking MLP operating performance to oil is in most cases futile. Their stock prices and oil did move together for months, until that correlation broke down most inconveniently as oil rose. Investors feel duped.

Many callers were looking for confirmation that they’re not missing something, so absent were compelling explanations. Is it tax reform? Little detail is known, but the Administration has proposed allowing owners of partnerships to pay taxes at newly reduced corporate rates rather than the higher ones on income (see MLPs and Tax Reform). And anyway, the MLPA is well practiced at lobbying against adverse tax changes.

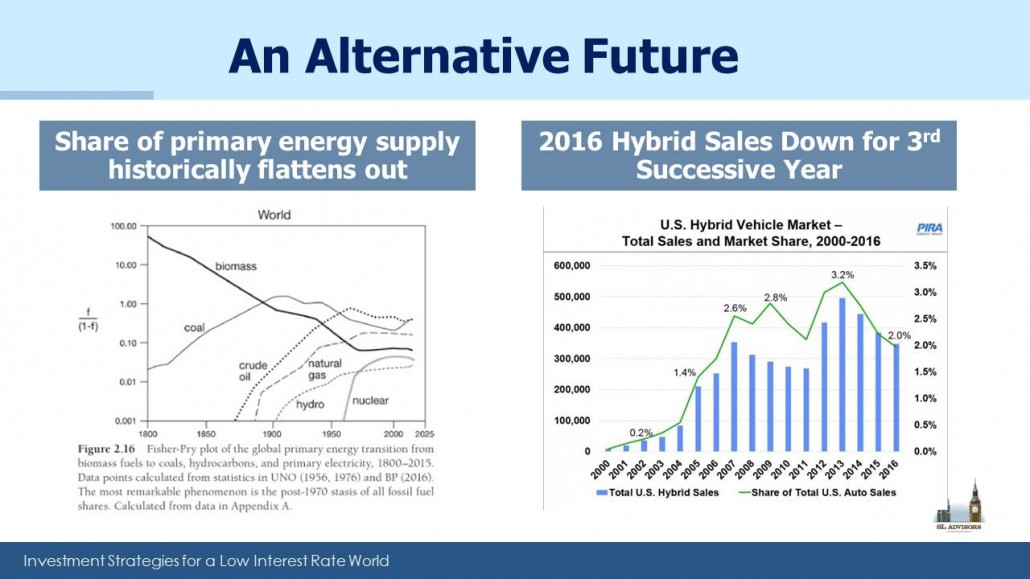

Perhaps investors are looking ahead to declining global crude oil demand? It’s a long way off and in any case US output looks set to exceed it previous high of 10 Million Barrels per Day next year, eclipsing a record set in 1970.

Is shale output peaking? The rig count is growing but more slowly. But looking across a broad selection of exploration and production companies, capex plans for 2018 don’t show much sign of retrenchment.

Tax loss selling was suggested by some — energy stocks offer many of the rather limited opportunities this year to sell at a tax-deductible loss. As MLP investors are painfully aware, the stock market has been registering new all-time highs seemingly every week. Hedge fund selling was certainly cited in some quarters, but there are a lot of hedge funds and they’re always buying and selling.

BP’s IPO of its refining business was probably responsible for some selling as investors created room by liquidating other positions. We didn’t participate and it doesn’t look as if we missed an opportunity since it quickly traded below its initial pricing.

Enterprise Products (EPD) used an announced future buyback to redirect cashflow back into new projects (see Why Don’t MLPs Do Buybacks?). It’s reflective of the shifting financing model. An Energy infrastructure sector with opportunities to reinvest in its business is redirecting cash from payouts to capex. It’s disillusioning to the income-seeking investor but is a sensible move if the returns are attractive. The continuing shift from income-seeking to growth-oriented investors is disruptive (see The Changing MLP Investor and More on the Changing MLP Investor), and is a major theme driving recent returns.

Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) yields over 13%. It’s a safe bet that a year from now its yield will be lower, either because the investor skepticism such a yield demonstrates is proven correct and it’s cut, or because buyers scoop up the stock and drive the yield lower. Yesterday, in an act of willful defiance aimed at the skeptics, Energy Transfer raised the dividend both on the GP, Energy Transfer Equity (ETE), and ETP.

Investing usually involves making a decision with adequate information but not all the knowledge one might like. There’s consequently a certain paranoia that, when things don’t go as expected, it’s because others (usually those selling) had some insight overlooked by the buyer. This can be a valuable self-protective instinct. The trader who concludes he knows all that’s needed to trade profitably is usually an ex-trader before too long. Many clients were explicitly or implicitly worried that this might be the case.

But while a certain amount of paranoia can be useful, it’s not always correct that a mark to market loss proves an analytical oversight. We continue to scour for tangible justifications behind the recent move, so far with limited success. We’ve talked to investors in the last week who are buying, holding and selling. The first two are easy to justify on valuation terms even though it takes a brave soul to risk capital under current circumstances. But the sellers we’ve chatted to know little more than the first two categories. What they do know is that they’ve had enough. They feel aggrieved that a correctly constructive view on oil prices has been destructive. They are tired of their clients asking why, in such a buoyant equity market, they own stocks that are falling. They’re fed up with missing the action. Maybe valuations are compelling but they’re no longer of a mind to wait for other buyers to act on this. They don’t possess more facts than the buyers, they’ve simply run out of patience.

It’s a pity, and will probably look like an emotional decision over the long run. But it sure felt good earlier in the week, and may well look brilliant following another week of selling.

Market timing is rarely easy, and so we remain invested because valuations are more attractive in energy infrastructure than any other sector. Don’t use leverage. Pick companies and sectors with strong balance sheets. This enables waiting out the inevitable swoons that over-managing positions causes.

We are invested in EPD and ETE