The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power was first published 27 years ago, although Daniel Yergin added an Epilogue in 2008. It is nothing less than an economic and political history of crude oil. At 910 pages of text and footnotes it’s an epic read, but you can select sections of interest and jump around, leaving and returning to it later. The very beginnings of the U.S. oil business were about producing kerosene from “rock oil” to replace whale oil or turpentine used for light. Its illuminative qualities were deemed far superior to the alternatives and production took off in the early 1860s. The Civil War boosted demand and the oil business had begun. John D. Rockefeller became the richest man in America by selling kerosene.

During the early 1900s the internal combustion engine created a new market for gasoline, promoting oil in importance over coal as a source of primary energy and leading Daniel Yergin to dub the 20th Century “The Age of Oil”.

The 1973 Oil Shock is a distant memory for those of us old enough to have any first hand recollection. It’s therefore quite sobering to re-familiarize oneself with its history as recounted by Yergin in 1990 when its ramifications remained fresh. Iconic photos of cars lined up outside gas stations were a vivid reminder of modern society’s dependence on oil; they also exposed the western world’s sudden vulnerability to an adverse clash of politics and economics in a volatile region.

Reading about events some 44 years later, the ability of Arab oil producers to turn a spigot so as to influence U.S. policy decisions was outrageous, an affront. The history of how OPEC came to wield such power is well recounted by Yergin. From 1948-72, 70% of newly discovered proved oil reserves were located in the Middle East. This concentration of oil resources combined with western governments’ inattention to their increasing reliance on monarchs with whom their interests were not aligned created the conditions under which the Arab Oil Embargo was so effective.

Countries were placed on one of three lists (Friendly, Neutral or Unfriendly) depending on how closely their public policy statements pleased Arab oil suppliers, with deliveries modified commensurately. Europe produced very little oil and Japan virtually none. By contrast, U.S. production reached 9.5 Million Barrels per day (MMB/D) in 1973, coincidentally, a record we will soon eclipse.

Although America wasn’t self-sufficient, it wasn’t as reliant on OPEC as others. However, strong domestic demand had caused imports to almost triple over the prior six years, to 6 MMB/D, so energy independence was not a realistic objective. Over the prior quarter century the U.S. share of world production had fallen from 64% to 22% as Middle East nations ramped up their output from 1.1 MMB/D to 18.2 MMB/D.

The 1973 Arab Oil Embargo was a political and economic shock, and ever since the U.S. has paid close attention to the region. The 1990-91 Gulf War fought to eject Iran from Kuwait was arguably all about oil reserves, and the U.S. continues to maintain a large military presence in the area. Yergin’s book had the good fortune to be published in December 1990, just a month before the U.S. and its allies launched Desert Storm. There is an eight episode documentary accompanying Yergin’s book that can be found on Youtube. It was shown on PBS in 1992-93, a couple of years after the book’s publication, and provides interviews with many of the oil executives and government officials involved at that time. One U.S. oil CEO had expected public opinion to demand less reliance on imported energy following 1973, and the second oil shock in 1979 after the Iranian revolution. But diversity of supply lessened OPEC’s power, and the Gulf War showed that Middle Eastern oil reserves couldn’t be seized by an unfriendly power.

Nonetheless, I found that reliving those events through Yergin’s book and documentary provoked feelings of outrage, and a wish that we never again find ourselves so vulnerable to others.

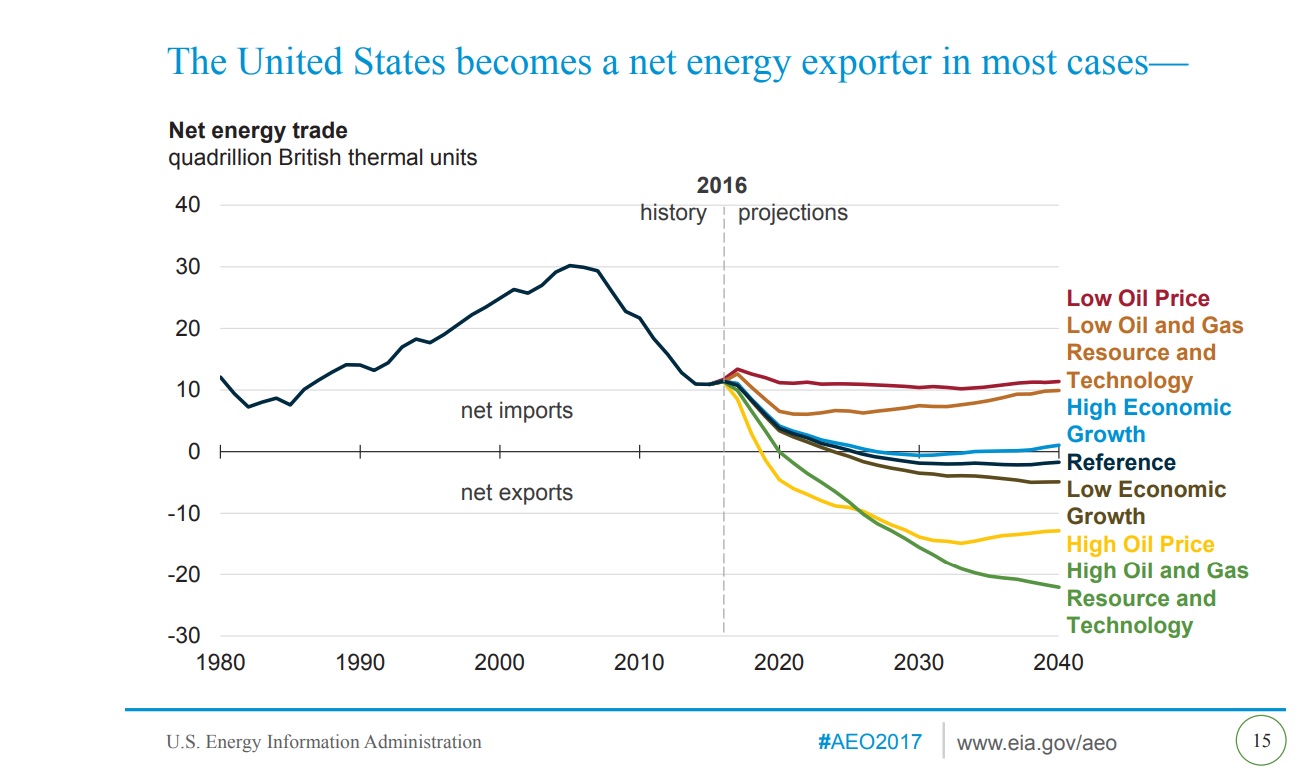

And guess what? American Energy Independence, for generations no more than an aspirational state, is clearly now in America’s future. It has multiple definitions – the Energy Information Agency (EIA) defines this as BTU independent, which means that we are a net exporter of energy in all its forms once they’re converted to their energy-equivalent, BTU content. The EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook 2017 projects that we shall achieve BTU-independence within the next decade. We recently achieved Natural Gas independence, as exports began exceeding imports over the past twelve months. Shipments of Liquified Natural Gas are set to rise substantially in coming years as new liquefaction plants become operational. We’ve long been a net exporter of coal.

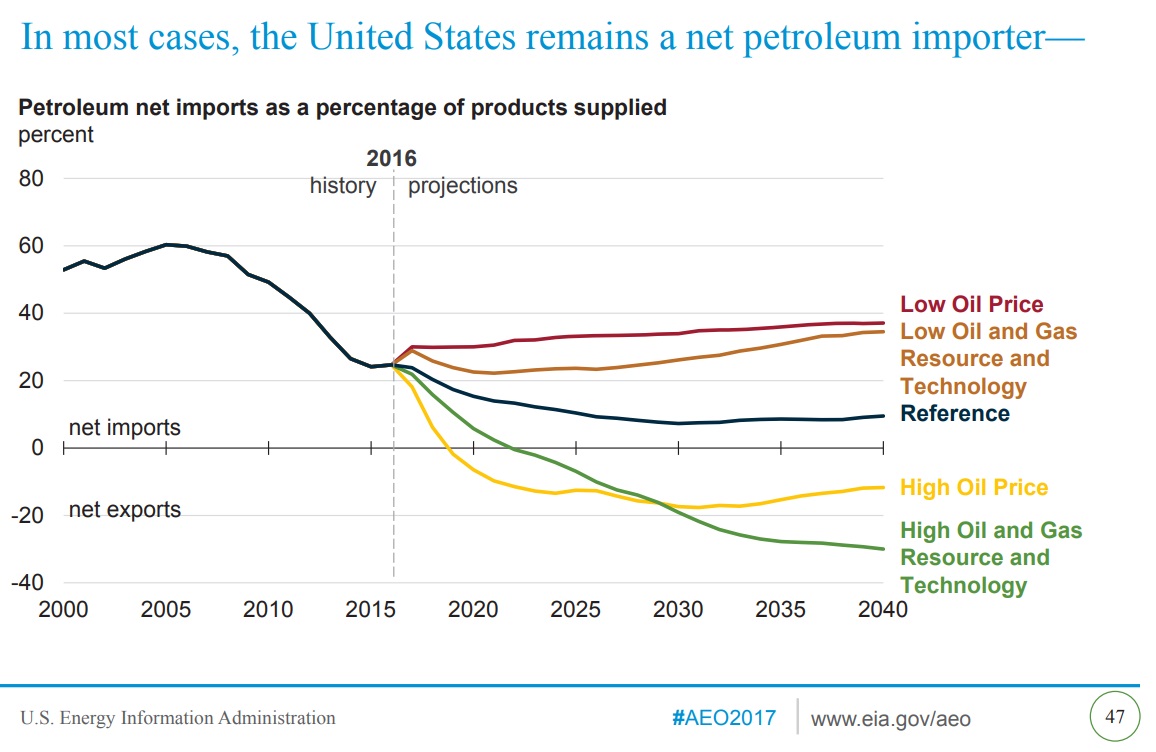

Although BTU-independence is the most complete measure of our reliance on others for energy, most casual observers think simply in terms of oil independence, especially given the contemporary history recounted by Daniel Yergin. Photos of drivers sitting in gas lines remain an emotive image. The EIA makes a Reference Case forecast (its Base Case) but includes other less likely but still plausible scenarios. Their central expectation is for the U.S. to remain a net importer of petroleum products (defined as crude oil, refined products and natural gas liquids), albeit at a steadily diminishing rate, falling by two thirds within a decade.

But if crude prices rise higher than they expect, or improvements in the technology driving shale oil and gas output surprise to the upside, the U.S. could become a substantial net exporter. OPEC long ago lost its ability to call the shots and in recent years their inability to set prices has been amply demonstrated. This is the enormity of the Shale Revolution. Its impact is far more than simply economic, although in that respect it’s already substantial. Its geopolitical effects will continue to reverberate through different countries’ needs for energy security. U.S. policy in the Middle East will reflect a reduced reliance on the region’s major export, something Americans will overwhelmingly welcome.

In a recent interview on the Shale Revolution, Yergin cited the sanctions imposed on Iran as an example of shifting energy power. He asserted that without the growth in U.S. oil production, the removal of Iranian oil supplies from the market would have been unworkable. Yergin has found that in discussions with foreign decision makers across Europe and Asia, there is a recognition that America’s role in the world is changing, in part because of improved security around energy supplies.

Today we’re seeing an alignment of resources, technology and public policy that together are bringing a seemingly Utopian vision closer to reality. Energy infrastructure is growing as it adapts to increased production that is supplying new markets. It may have taken half a century, but the dynamism of American capitalism is denying the ability of foreign despots or hostile governments to inflict substantial economic harm through manipulating energy exports.