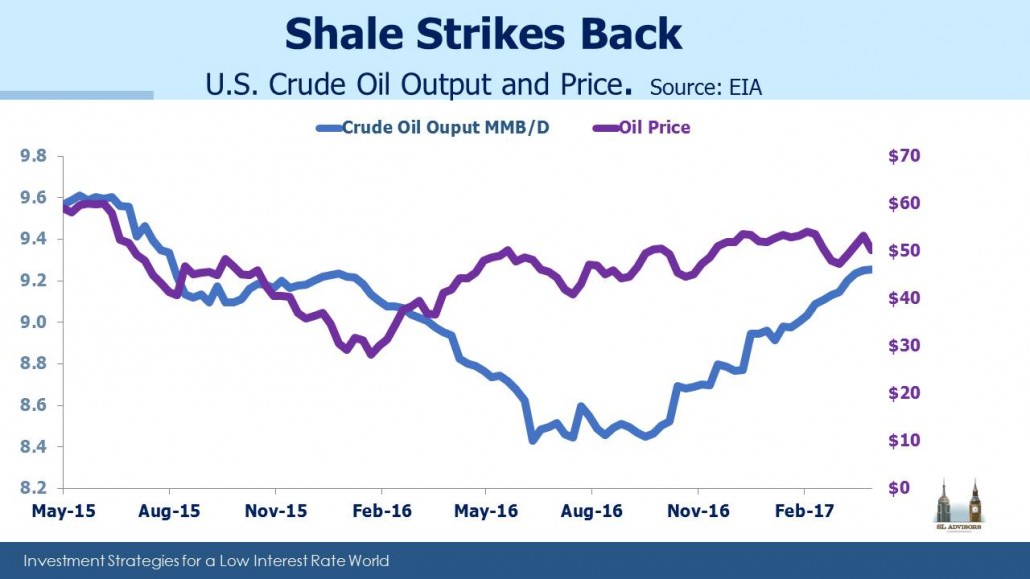

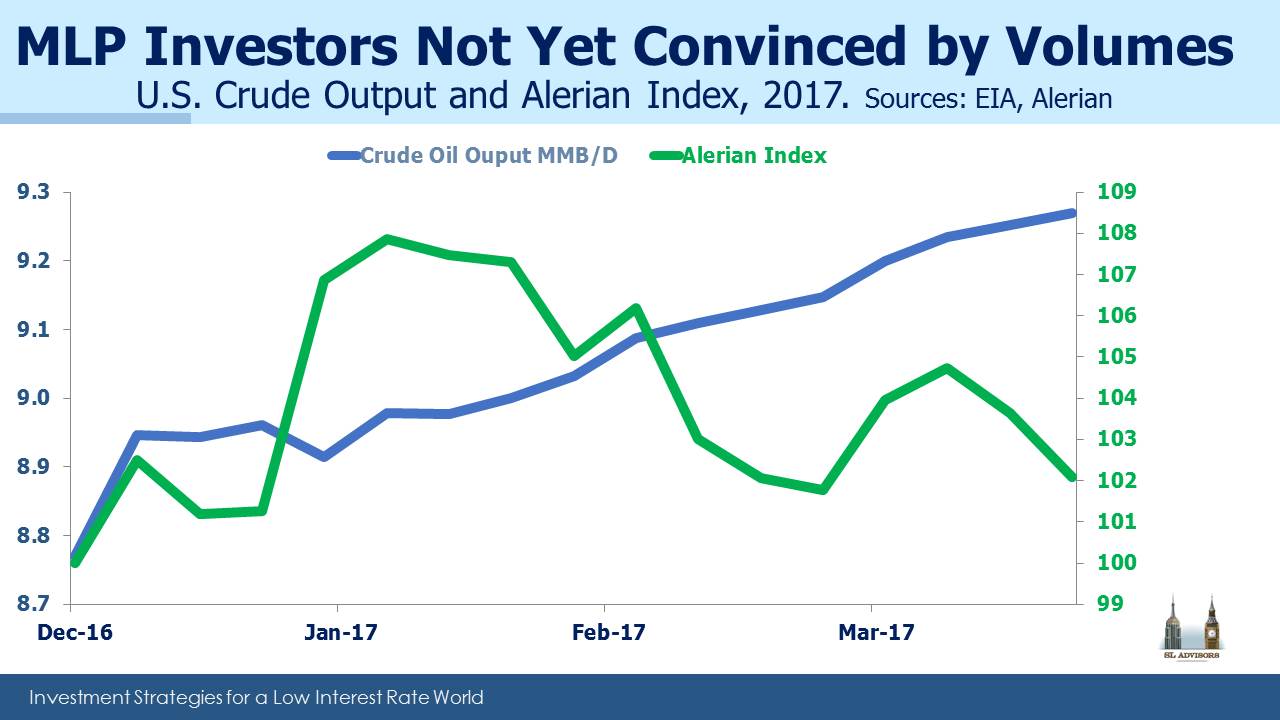

| Recent weakness in crude oil has spilled over into Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs). Some connection between the two is understandable, because part of the bull case for MLPs lies in growing shale output increasing demand for energy infrastructure. Lower oil prices dampen the enthusiasm for the idea that Exploration and Production (E&P) companies will be competing for sometimes scarce pipeline resources. For our part, we think the short-cycle nature of shale offers a substantial advantage for producers (see What Matters More, Price or Volumes?). MLP investors often feel they must have a view on crude oil before investing; because U.S. volumes are likely to rise in almost any price scenario, we think it’s less important other than over the short term perhaps. Shifting your MLP exposure around in response to oil prices is not a good long term strategy. If you have a view on oil, invest in oil.

Profiting from owning crude oil is harder than you might think. Many ignore storage costs. While these aren’t directly reflected in spot prices, they are most assuredly part of the return from owning securities linked to the price of oil. The costly “rolldown”, by which the expiring near futures contract has to be regularly rolled into the next, higher priced one simply reflects the cost of storage. The approximately $1.20 per barrel price difference between May and August crude futures is largely due to the cost of storage for three months. Think of it as the time value of money applied to crude oil.

Exchange traded products linked to oil have a checkered past, which some think shows the need for a better solution aimed at those who would like to profit from their view of oil prices. ProShares, a purveyor of leveraged ETFs, has come up with a doozy.

Oil has been pretty volatile over the last few years. From its peak in 2014 its spot price dropped by 75% through February 2016, before doubling over the next year. If your version of excitement is a commodity price that gyrates wildly, you need look no further than oil futures.

But some find this tame. Downhill skiing may appear sedentary to those who insist a true mountain experience must be preceded by a helicopter ride to find real deep powder. But the kite skier needs a three-dimensional snow experience; if it’s not dangerous it’s not worth the trouble.

The kite skier is the type of buyer attracted to the ProShares UltraPro 3x Long Crude Oil ETF, designed for those wanting to profit from rising crude oil (Ticker: OILU). And because excitement need not be limited to a rising market, they also have a bear market version (Ticker: OILD).

These two investments share a couple of traits with kite-skiing, in that they’re dangerous and not everyone involved will have a good time. OILU is designed to move each day by three times the percentage move in the Bloomberg WTI Crude Oil Sub-index. In order to maintain this 3X exposure to daily moves, OILU will need to rebalance its holdings every day. Without going into the messy details, this introduces the insidious nature of the use of leverage, in that rebalancing will always necessitate trading in the direction of the market. Following a rise in crude, they’ll need to buy more oil futures to bring their exposure back up to 3X. When it falls, they’ll need to sell oil to bring their exposure down to 3X.

As you can appreciate, if oil goes up and down but doesn’t make much overall progress, the buy high/sell low rhythm of re-hedging will relentlessly eat away at the holder’s value.

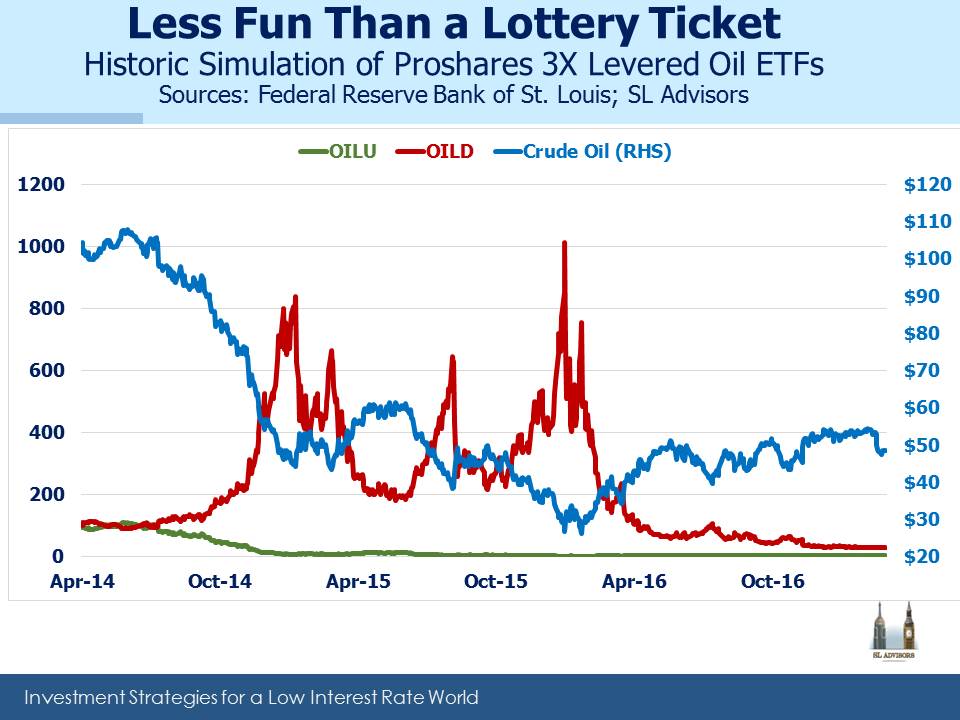

The last couple of years were interesting to say the least for oil traders. It’s possible to simulate how OILU and OILD would have performed for their holders over this period. The simulation omits fees and transactions costs, so the real results would have been a bit worse.

It might not surprise to learn that OILU lost money when oil went down. It is after all designed to make money if oil rises, so if your forecast is wrong OILU will not be your friend. Crude peaked in April 2014, and OILU would have lost 90% of its value by Christmas. Its chart looks rather like a kite skier suffering cardiac arrest. Although it’s hard to see, I can report that OILU did double in price when oil began to rally, albeit after falling 95%.

More surprising is that the bear market version, OILD, ultimately fared little better. Although crude oil is roughly half its value from three years ago, the OILD holder who made this correct forecast nonetheless saw his investment lose 70% of its value.

The point here is that 3X levered ETFs are not for those who develop an emotional attachment to their securities. The longer your holding period, the greater the certainty that you will lose money. Therefore, the optimal holding period is correspondingly as short as possible – or, if you’re not a kite skier, no holding period at all. Leverage means you care not just about the accuracy of your forecast but also about how quickly it happens. Predicting the near term path of prices as well as their ultimate resolution is how the over-confident are separated from their money. Leveraged ETFs are designed with the expectation that rebalancing will inexorably drive their value to zero.

The seductive and eye-catching part of the chart is of course the eightfold and eventually tenfold increase in the price of OILD. It was most definitely possible to make a lot of money from OILD. It required the possession of both oil price insight and exquisite timing, but for those blessed with both a healthy gain was to be had.

The problem is that, since few could have had such luck, over the three year simulation the typical holder lost money. Because ETFs don’t have a fixed share count some might quibble with this assertion; buying might have been substantial at low prices and inconsequential at high ones. It is unknowable of course, but in securities markets activity inevitably rises with prices. There would have most likely been many more buyers of these levered ETFs when they’d risen, further increasing the ranks of ultimate losers.

So you have a product that will be profitable for some but unprofitable for many and certainly for most. Should it even exist? How should we regard the supplier of something of whom the customers will for the most part suffer financially from their purchase? Is ProShares part of the efficient channeling of savings towards productive capital formation, the reason public capital markets exist? Or are they the casino owner, profiting from customers who on average will be richer by not entering?

And what’s wrong with that? Lottery ticket buyers, even the least financially sophisticated, pretty much understand that the odds are against them. In willful defiance of classical economic theory, lotteries nonetheless thrive even though the customers are selecting negative expected outcomes. They do this because the hope of winning, the dreaming of how that payoff would transform life, itself comes with positive utility. No ticket, no dream. Hope has value.

Is it therefore also true that users of ProShares products similarly comprehend the adverse odds they face and nonetheless derive utility from the hope of profit? Or is it more likely that they don’t perform the analysis above, and attribute any financial outcome to their expressed opinion rather than poor choice of product? In this case, the buyers of ProShares 3X products are less financially sophisticated than the lottery buyers they might regard with disdain. When waiting in 7-11 to buy milk while a customer ahead purchases a lottery ticket, the ProShares buyer should seek his financial advice. He might learn something. Lottery ticket buyers have more realistic expectations than ProShares buyers.

The ProShares prospectus details various dire outcomes that may result from a purchase. But of course nobody reads prospectuses, so they are legally compliant if not informative. However, shouldn’t there be a presumption that the typical holder of a ProShares product will profit if his underlying view is correct? What use is a supplier of financial products that largely destroy value? Demand certainly exists, as ProShares proudly notes on its website the $27BN in such ETFs they offer. But size of capital raised doesn’t prove intelligence by the investors, as the hedge fund industry routinely proves.

If some regard “ethical financier” as an oxymoron, it might be in part because of the values behind the offering of 3X leveraged ETFs. Just because something can be created doesn’t mean it should be. |