MLP Managements Talk Business

MLP managements have been verbose in the last couple of weeks. This is mostly due to the fact that it’s earnings season and conference calls provide an opportunity for investors to obtain additional color from senior executives. It’s the topic of our March newsletter which will be published on Tuesday, but there are many more interesting statements than the newsletter can accommodate.

The elephant in the MLP room is whether distributions will be maintained. Some of the yields are almost willfully defiant, in that they challenge the analyst to hold an opinion. For example, Energy Transfer Equity (ETE) yields 16.7% as of Friday’s close. This is almost certainly a temporary yield; bears will argue it is unsustainable and the distribution will be cut, while bulls will maintain that it is secure. A year from now ETE will probably have moved sharply in one direction or another depending on which view prevails. It is hard to be ambivalent about a 16.7% yield. This is a market that demands strong opinions. Some simple Math shows that if you buy a security yielding 16.7% and over the following year its yield drops by 2% due to price appreciation (reliably paying that 16.7% yield for a year will likely draw in new buyers), your total return is 30%. MLPs should offer this type of possible return, because recent weeks have shown that a 16.7% yield can be offset by a few bad days. But considering the paucity of return potential across other asset classes, it’s hard to see how any serious investor can evaluate her choices without thinking pretty hard about this sector. You may reject a possible 30% one year return as not worth the risk or unattainable, but a failure to consider it is lazy. A 16.7% yield challenges the observer to investigate further.

ETE’s CEO Kelcy Warren naturally maintains that the payout is secure, allowing himself virtually no wiggle room. While asserting that no distribution cuts were contemplated across the Energy Transfer complex, he said, “Our distribution cuts are not required at ETE. And we take our obligation to our unitholders very, very seriously. We have a duty to maintain our distributions. But everybody knows, obviously, that’s an option to the extent of that we need access to distributions to maintain our financial health at ETE; would we reach in to that bucket, it would be the last one we’d reach to, but it’s certainly possible.” Of course, no CEO highlights the likelihood of a cut until it’s done, at which time it appears inevitable. We’ve made our bet, because managements at ETE and other businesses are reducing capex, eliminating their need for new equity and paying close attention to the ability of cashflows to service debt and continue distributions. They are generally doing the right thing. So we side with Kelcy. But it’s also true that while a distribution cut represents a betrayal of your investors, if the cash is used to fund accretive growth projects so as to avoid the dilution from issuing additional equity, as Kinder Morgan (KMI) argued, there’s nothing theoretically destructive to value. On December 8, the day KMI announced its dividend cut, the stock closed at $15.72 and is now at $17.76. Berkshire Hathaway (BRK) doesn’t need stocks that pay high dividends; their challenge is finding good places to invest their cash, and KMI’s subsequent reliance on internally generated cash to finance growth probably made them more attractive in Omaha.

Cheniere’s LNG export facility in Sabine Pass, LA exported its first batch of natural gas last week. The Wall Street Journal published an insightful article highlighting the attractiveness of the U.S. as a supplier to countries such as Lithuania, who are tiring of Gazprom’s hard-line negotiations that typically start on New Year’s Eve when the threat of a mid-winter supply disruption hangs over the price discussions.

The photo is a satellite shot of the U.S. at night, and while most of the lights are in population areas the white box highlights North Dakota where there are few people but lots of gas flaring. Oneok’s CEO Terry Spencer commented this week, “So flared gas, let me just tell you, it’s not an exact science. And it’s quite possible we could have more flared gas than we actually believe we have, because every time we turn on a compressor station it seems like the wells behind that particular compressor station outperform our expectations. Time and time again, more gas is showing up than what we thought.” Since flaring is both bad for the environment as well as commercially destructive, those in favor of additional infrastructure to capture this lost output must include environmentalists, involved E&P companies and indirectly the Lithuanian electricity consumer. The U.S. is on its way to becoming a significant exporter of hydrocarbons, and its reliability will compare favorably with many of the competing exporters. If you choose not to buy from unstable regions or unpredictable kleptocracies, your choices of supply can be limited. The shifting geopolitics is the long game, but is hardly reflected in today’s asset prices.

We are invested in BRK, ETE, KMI and OKE

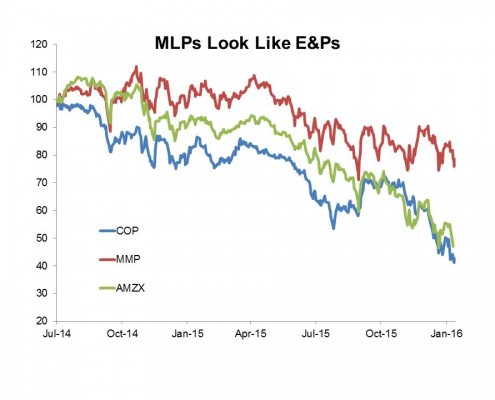

Around ten days ago Conoco Phillips (COP) and Magellan Midstream (MMP) both released their 4Q15 earnings, and held conference calls on February 4th to discuss them. This coincidence of reporting is about all they have in common, but it caused us to look a bit more closely at an energy company (COP) that truly has commodity price exposure and what it’s doing about it.

Around ten days ago Conoco Phillips (COP) and Magellan Midstream (MMP) both released their 4Q15 earnings, and held conference calls on February 4th to discuss them. This coincidence of reporting is about all they have in common, but it caused us to look a bit more closely at an energy company (COP) that truly has commodity price exposure and what it’s doing about it.