Bond Yields Reach Another Milestone

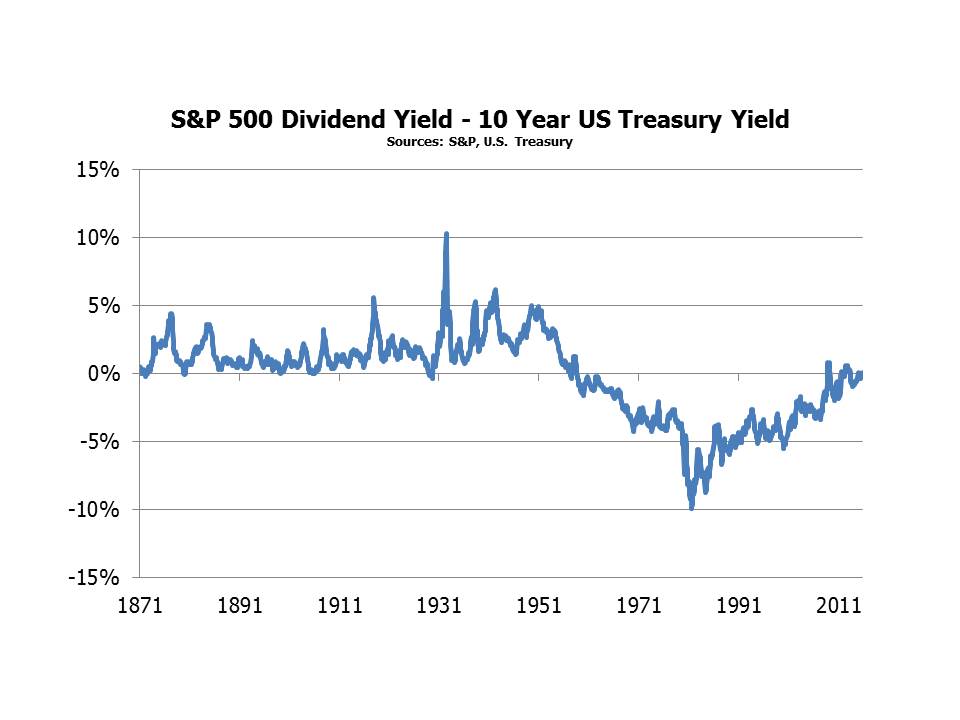

Recently, an important threshold was breached in terms of relative valuation between stocks and bonds. The yield on ten year U.S. treasuries drifted below the dividend yield on the S&P 500. It’s happened a couple of times in recent years but only because of a flight to quality and never for very long. This time looks different.

It’s worth examining this relationship over a very long period of time. The chart below goes back to 1871 and reminds us that for decades stock dividends were regarded as risky and uncertain. Little attention was paid to the possibility of dividend growth, and investors clearly placed greater value on the security of coupon payments from bonds.

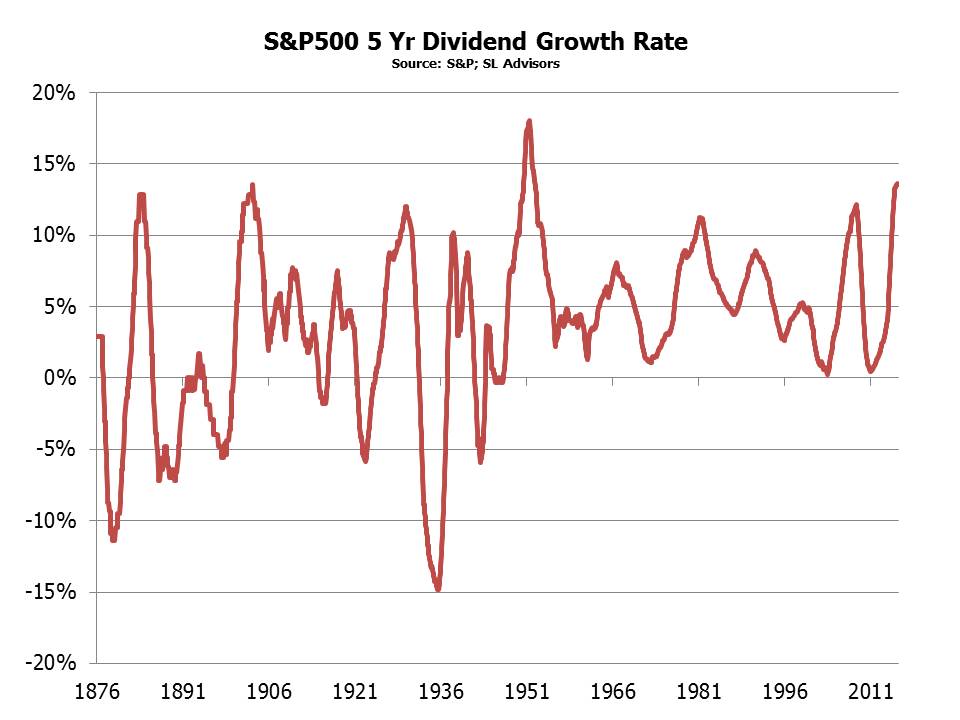

This spread began to reverse in the late 1950s and since then, during the careers of a substantial percentage of today’s investors, bond yields have remained the higher of the two. Dividend growth (defined as the trailing five year annualized growth rate) was more variable prior to the 1950s with several periods when it was negative, so it’s understandable that investors of the day regarded dividends as quite uncertain. However, since the S&P500 dividend yield dipped below treasury yields, dividend growth has never been negative. The five year annualized growth rate since 1960 is 5.8%. Assessing a long term return target for equities is inevitably a combination of art and science, but adding a 5% growth rate to today’s 2% dividend yield suggests 7% is a defensible assumed return.

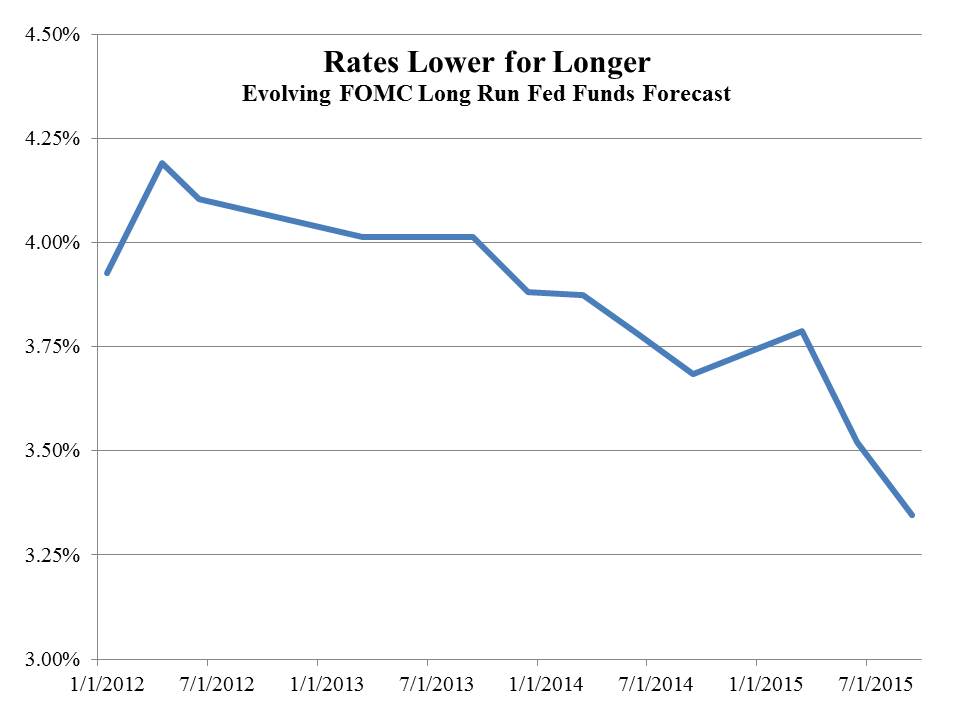

The trend of bond yields to decline towards dividend yields began a long time ago – back in 1981 when interest rates and inflation were peaking. It’s taken over 30 years, but the relationship is now back where it was during the Korean War. The investment outlook is, as always, uncertain with multiple areas of concern. However, the Federal Open Market Committee has made it abundantly clear that rates will rise slowly; recent earnings reports from Coke (KO), Dow Chemical (DOW), Microsoft (MSFT) and Amazon (AMZN) have all been good. These and many other stocks are near 52-week highs and in some cases all-time highs. FactSet projects earnings and dividends to grow mid to high single digits over the next year. These considerations are once again highlighting the inadequacy of fixed return securities as a source of after-tax real returns, and with one major asset class devoid of any value investors are again turning to stocks. The tumultuous markets of late August and September are receding; rather than portending a coming economic collapse, they simply represent additional evidence that far too much capital employs leverage.

The long term trend suggests that treasury yields will remain below dividend yields for the foreseeable future. We’re not forecasting such, simply noting that a 2% yield that is likely to grow on a diversified portfolio of stocks looks a whole lot more attractive than a 2% yield that’s fixed. It didn’t look so smart in recent weeks, but if you don’t use leverage and restrict yourself to companies with strong balance sheets you can watch such shenanigans from the sidelines.

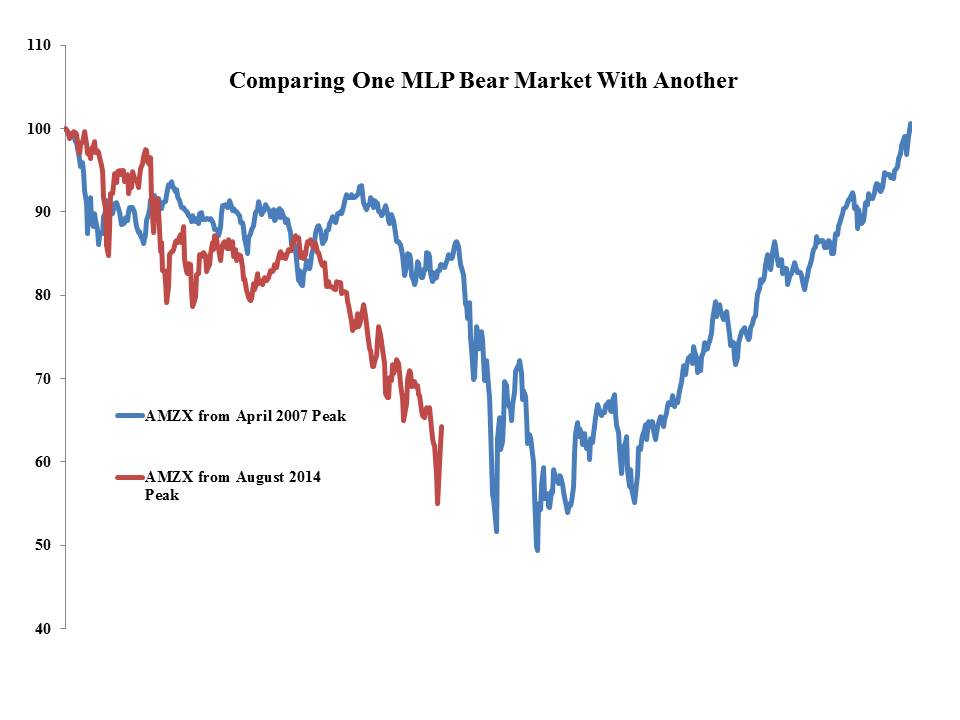

Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs) have begun reporting earnings. Kinder Morgan (KMI) disappointed investors by trimming their 2016 dividend growth from 10% to 6-10%. KMI isn’t technically an MLP any more since they reorganized into a C-corp last year. However, they are squarely in the energy infrastructure business like midstream MLPs. Rather than issue equity to fund their growth projects, they plan to access an alternate, not yet disclosed source of capital through the middle of next year. Their free cashflow covers their distribution, and they access the capital markets to finance growth.

MLPs have had a torrid year, with the sector down far more (in our view) than lower crude oil would justify. As Rich Kinder said, “…we are insulated from the direct and indirect impacts of very low commodity environment, but we are not immune.” KMI owns pipelines and terminals; 54% of their cashflows come from natural gas pipelines; 11% come from a CO2 business that supports oil production; they transport about a third of the natural gas consumed in the U.S. 96% of their cashflows are fee-based or hedged: “insulated…but not immune”.

Selling energy infrastructure stocks is fashionable, and owning them is not. While bond yields are dipping below the S&P’s 2% dividend yield, KMI yields more than three times as much (7.25% on its 2016 dividend assuming the low end of the 6-10% growth range) and its dividend will grow at least as fast. Owning such securities will once more be fashionable.

We are invested in KO, DOW and KMI.