Why MLPs Make a Great Christmas Present

Using such a cheery headline following the week MLPs have had will tempt wisecracks that Christmas tree baubles might be better investments than MLPs. Nonetheless, your blogger is looking beyond the latest round of forced selling and taking the longer-term view on returns. It is likely that buyers better understand the values they are getting than sellers do the values they are rejecting. Midstream MLPs with little or no crude oil exposure have seen their equity prices fall. Even StonMore (STON) an MLP in the “deathcare” business, has revealed unexpected linkage between WTI crude and dying. It is in any case hard to explain recent moves beyond noting that sellers evidently seized their task with greater urgency than buyers.

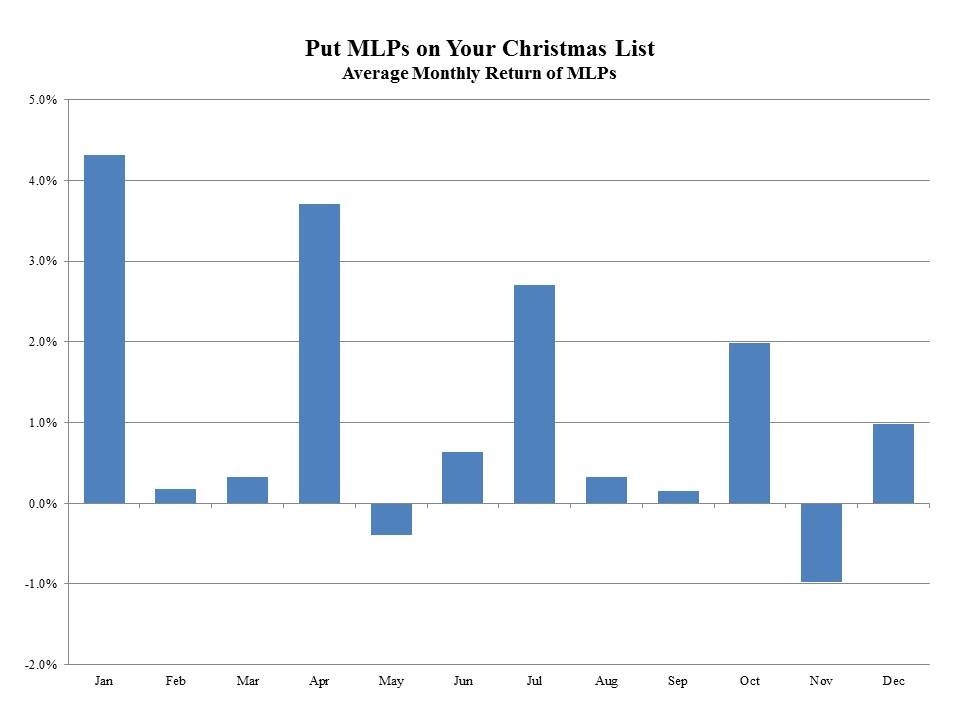

Seasonal patterns in financial markets can draw great interest. The January effect in stocks is well known if less commonly experienced; other folklore includes the adage to avoid selling on Mondays (presumably because a weekend of stressing over a poor investment induces action as soon as possible). As is often the case with statistics, identifying correlation without causality will part many a superficial investor from his capital. There needs to be an economic explanation for an effect for it to mean anything.

Many investors plan their allocations around year-end, but this is especially so for retail investors for whom Christmas offers some time to contemplate finances while recovering from an excess of merriment and (perhaps) family togetherness. Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs) remain widely held by individuals; hence the seasonal pattern they exhibit is both valid and pronounced.

A dilemma for investors is approaching. As we close in on only the second worst year in the history of the Alerian Index (since January 1996), do they forget the pain so far and add, or lick their wounds and wait. The average monthly return on the Alerian Index is 1.17%, although 2015 provided numerous results inferior to that. November is seasonally the worst month, with an average return of -1.0%. December tends to be average, but January averages +4.3%. On average, being invested only for the two months of December and January provides over a third of the annual return .

.

Of course, there’s always more detail to consider; November’s average return is the worst because it includes November 2008’s -17.1% drubbing. That month alone knocks the November average down by 0.27%. Then again, January’s average is helped by the January 2009 result of +15.25%, which adds 0.55% to January’s average. You can of course include and exclude months variously and get different results, the validity of which is to a person’s taste.

Nonetheless, the clear pattern is that MLP investors tend to buy (or sell less) in the first month of every quarter. This is probably because it coincides with quarterly distributions. The quarterly affect is magnified by the turning of the calendar.

Around this time of year, we advise MLP clients that if they’re contemplating making a commitment the seasonals suggest doing so in November, when prices are weak. If you’re a seller it makes sense to wait for January, since so few sellers seem to be available then.

The seasonals have not worked so well the last couple of years. Whether this is because they’re now so well known that they no longer work won’t be clear for a while longer. However, I’d bet that the universe of MLP sellers waiting until December or January to act is fairly small. If the recent price dislocations didn’t yet force you out, you’re probably in for the very long run. By contrast, the paucity of available sources of yield should draw reallocations towards a very cheap sector from investors digesting their Christmas dinner and pondering where their 2016 returns will come from.

Please remember that past performance is not indicative of future returns.